Physiology Of The Large Intestine

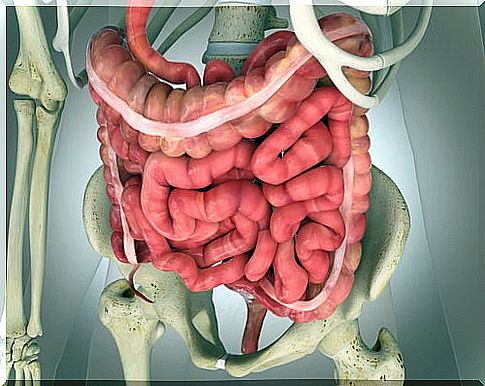

In order to proceed with the review of what constitutes the physiology of the large intestine, it is necessary to remember that we are referring specifically to the final section of the digestive tract, which is made up of the following: cecum, colon, rectum and anal canal. In short, they constitute the widest and shortest part of the digestive tract.

The large intestine has the function of absorbing water and electrolytes. The more proximal half is responsible for this function. On the other hand, the storage of fecal matter until its expulsion, of which the most distal half is responsible.

These functions do not require the peristaltic movements made by the colon to be as intense as in previous sections. In fact, these are slow and smooth . Still, colon movements have characteristics similar to small bowel movements.

Physiology of the Large Intestine: Colon Movements

As in the small intestine, the movements of the colon can be divided into mixing movements and propulsion movements. This is stated in this report from the University of Cantabria.

The mixing movements are explained by the combined contraction of the circular muscle and the longitudinal muscle of the colon. This causes the unstimulated portion of the colon to protrude outward like a sac called a haustra.

The propulsion movements depend on the “mass movements ”. It is a modified type of peristalsis that causes a segment of the colon to act as a unit, pushing fecal material forward. These movements occur 3 times a day, lasting about 30 minutes each time.

How do these movements start?

Mass movements occur in response to distention of the stomach and duodenum. At other times, in response to irritation, as occurs in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Physiology of the large intestine: defecation reflexes

The expulsion of stool is due to defecation reflexes:

- Intrinsic reflex: directed by the enteric nervous system of the rectum itself (by itself it is too weak).

- Parasympathetic reflex: controlled by the fibers of the pelvic nerves and which acts as a reinforcement.

How does it happen?

The arrival of stool into the rectum causes a distention of its wall, which sends afferent signals through the myenteric plexus. In response to this, peristaltic waves are initiated from the descending colon to the rectum that propel stool into the anus.

The myenteric plexus emits inhibitory signals that relax the internal anal sphincter. Thus, when the peristaltic wave reaches the anus, the stool continues to advance. Relaxation of the external anal sphincter is done consciously.

On the other hand, when the nerve fibers of the anus are stimulated, afferent signals are emitted towards the medulla. These return through the parasympathetic nerve fibers of the pelvic nerves. As a consequence, they enhance peristalsis and help relax the internal anal sphincter.

Physiology of the large intestine: secretion of substances

Only mucus containing moderate amounts of bicarbonate ions (pH> 8) is secreted in the large intestine . The secretion of this mucus is carried out by characteristic mucous cells of the intestine. The secretion of bicarbonate is carried out by epithelial cells other than mucous membranes and is responsible for the alkaline pH of the mucus.

How is it produced?

Mucus secretion is mainly mediated by direct stimulation of mucous cells. This stimulation increases in response to other stimulation of the pelvic nerves.

Physiology of the large intestine: absorption of substances

Approximately 1500 mL of chyme reach the large intestine each day. Most of the water and electrolytes it contains are absorbed mostly in the proximal half of the colon, so that the expelled stool contains only about 100 mL of water and between 1 and 5 mEq of sodium and chlorine ions.

How are substances absorbed?

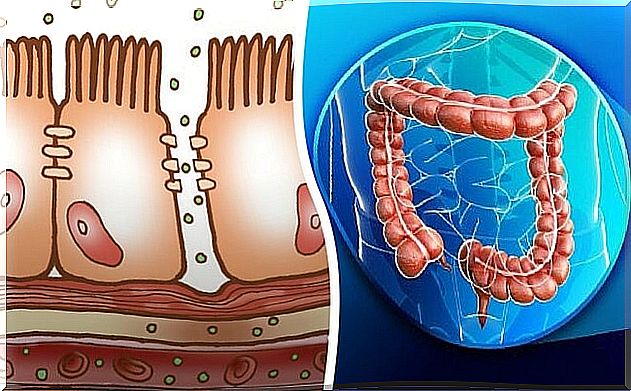

Sodium is absorbed by active transport through the Na / H exchanger, according to this study carried out by the National University of La Plata. Thanks to the positive charge gradient that originates, part of the chlorine ions are passively drawn into the cells. The rest of the chlorine ions are absorbed by exchange with bicarbonate ions.

The tight junctions between the cells of the large intestine are much tighter than in other sections of the digestive tract, thus avoiding the retrograde diffusion of ions and achieving a much more complete absorption of sodium.